Toward what does the arc of history bend?

Originally published in 2013 for Scapegoats and Panaceas.

Few things are as chilling as witnessing a former dictator or bureaucrat stand trial for genocide, torture, or other “crimes against humanity.” By now, such trials have become old hat.

Whether that fact attests to a general decline in political scruples, the absence of universally accepted code of ethics for war (is this possible, today?), or whether it means that the arc of history is bending, indeed, toward justice––I leave for you, dear reader, to decide. But the trial of General Efraín Ríos Montt in Guatemala, which starts today, is historic, in that it breaks the wall of impunity that has governed that country since the end of the 30-year civil war, notwithstanding the peace process and its truth commission, officially termed the project for “Historical Recuperation.” Beyond that, it is also significant for being only the third trial in a Latin American country to take on its own head of state.

Often the “arc of history” is so long that the perpetrators of such crimes are decrepit and old, barely capable of holding themselves up by the bones, by the time they are charged. After his 1998 arrest in London and charge in a Spanish court under the principle of universal jurisdiction, Augusto Pinochet was released and returned to Chile on the grounds of his alleged poor health. Ieng Thirith, charged with crimes against humanity due to her involvement with the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s, was ruled by the Cambodia Tribunal to be mentally unfit to stand trial due to her severe Alzheimer’s Disease. Comrade Duch, another high-level Khmer Rouge official, was sentenced by the same court to life in prison––which, at a frail 69 years old, might not be that long.

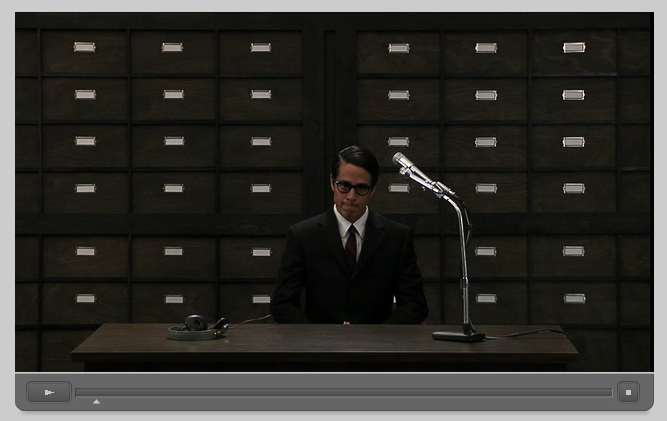

“Accused,” excerpt from Andrea Geyer’s video installation, “Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb, 2009.”

Based on the transcripts, video documentation and other accounts of the trial of Adolf Eichmann, including Hannah Arendt’s book “Eichmann in Jerusalem. A Report on the Banality of Evil.” http://bit.ly/VrYynv

Which is to say, such trials have a strange relationship indeed to history, to justice. Are they necessary? Are they important? Most certainly: in many ways (some dubious, but most legitimate) they allow for the beginnings of something like a sense of shared political space to be re-established. As Mark Vlasic puts it,

Looking back to the 20th century, few may have predicted that Slobodan Milosevic, Charles Taylor, Saddam Hussein, Radovan Karadzic, Ratko Mladić and Omar al-Bashir would have all been indicted for war crimes. But the fact that they have – and that someone like Comrade Duch has been found guilty of the atrocities that were committed in the 1970s – may support the presumption that the next generation of lawyers, prosecutors and foreign policy professionals may have the fortune of knowing a world in which high-level perpetrators are actually held accountable for their crimes.

Meanwhile, the legacy of violence and military rule remains deeply entrenched in post-dictatorship societies. In Guatemala, this entrenchment is evident in Ríos Montt’s own tenure in Congress until 2004, and in the brutal, unsolved murder of Bishop Gerardi, days after he spearheaded the release of a more expansive, unofficial report on perpetrators and victims of the genocidal civil war in 1998. As another example, newspapers in Brazil, which were varyingly complicit with the military regime, have in recent years called the dictatorship a “ditabranda” (branda = mild), which translates roughly as, “it wasn’t so bad”. In these and other contexts, one of the largest post-war questions has to do with how lower-level military, trained in the methodology of torture, disappearances, and other “counterinsurgency” techniques, transition back to civilian life, back to a kind of “peace.” In Guatemala at least, levels of violence in the civilian population have skyrocketed in the years since the war, with one of the highest rates of femicide worldwide, drug trafficking on the rise, and a hopeless backlog of unsolved, often un-investigated cases of political assassinations, kidnappings, and the like. Trials like the one beginning today won’t, at least very directly, do much at all to address these broader, more diffuse legacies of state terror. But maybe we can at least say that without such accountability on the higher levels, addressing those endemic problems doesn’t stand a chance.

Referring to footage taken by Pamela Yates twenty years ago that provided the lynchpin piece of evidence that led to Ríos Montt’s indictment, Kate Doyle, a senior analyst at the National Security Archive and expert witness for the case, gives her take on the relationship between accountability for past political crimes, and “justice” in the present:

The Ríos Montt trial will unfold within this polarized climate. The aging dictator’s defense lawyers will undoubtedly try to derail the case through pointless appeals, challenges of the court’s competence, and other legal maneuvers. But it will be impossible to halt altogether without provoking a storm of national and international outrage. Now that the indictment has been issued—making Guatemala one of only three countries in Latin America with the wherewithal to charge a head of state with human rights crimes (along with Peru and Uruguay)—the whole world is watching.

There is nothing more electrifying than seeing a former strongman forced to face his accusers in a court of law. Unless it is seeing an image of his younger self as it appeared 30 years ago, when he was at the height of his powers, projected by prosecutors onto the courtroom wall above him. The year was 1982, the interviewer was a young documentary filmmaker, and Ríos Montt was angrily denying the existence of military repression in Guatemala. His words now serve as evidence of his command authority over the scorched earth campaigns.

“If I can’t control the army,” he told his visitor, “then what am I doing here?”

It’s strange the role the bodies play in accounting for political conflicts of the past. The exhumed bodies of the disappeared take on new significance in the pursuit of justice and political transition; just as strangely, the body of the dictator becomes a technicality, an accident of birth, a mere detail in the drama of the historical moment. The body of the dictator enters the courtroom and occupies that space. Its weakness in that place belies the terrible power it wielded in the years of violence.

Ríos Montt is, and isn’t, that same arrogant young general that uttered those words, almost in passing, three decades ago. It took the same years that produced the sag in his shoulders, the gray hairs, the slight curve in his back, to bring about the historical conditions that would allow him to be tried by his own government.

https://scapegoatsandpanaceas.wordpress.com/2013/01/30/toward-what-does-the-arc-of-history-bend/